Will Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” as critics contend, be a massive giveaway to the rich?

Absolutely, when you tally it up. Yet the bill’s provisions, while devastating to the nation’s poorest, represent only modest gains for the majority of affluent families. Consider the merely rich—the top-earning 10 percent of households. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the House version of the bill will increase average after-tax resources of those families by about $12,000, or 2.3 percent—hardly life-changing for families that bring home an average of $522,000 a year after taxes. (It may well prove life-changing for families on Medicaid and food stamps, and not in a good way.)

And what of the “ultrawealthy”—which I’ll define as households with at least $100 million in assets, enough to break into the richest 0.01 percent? For them, the financial benefits are even less meaningful, amounting to maybe five days’ worth of growth in their asset portfolios—basically a rounding error.

Our tax code is based on a fiction—the idea that investment gains aren’t income until the underlying investments are sold.

All of which begs the question: Is America’s progressive income tax—enacted by Congress way back when in part to tame Gilded Age excess—even capable of curbing the wealth inequality now eating away at our social and political fabric?

The answer: a resounding no. Even if Congress were to create a 100 percent tax bracket for people with millions of dollars in earnings, their wealth would keep growing relative to everyone else’s.

That’s because the government’s definition of taxable income doesn’t track with true economic income, and this disconnect grows as one proceeds further up the wealth ladder. At the uppermost rungs, barely 10 percent of an ultrarich person’s economic income shows up on their 1040.

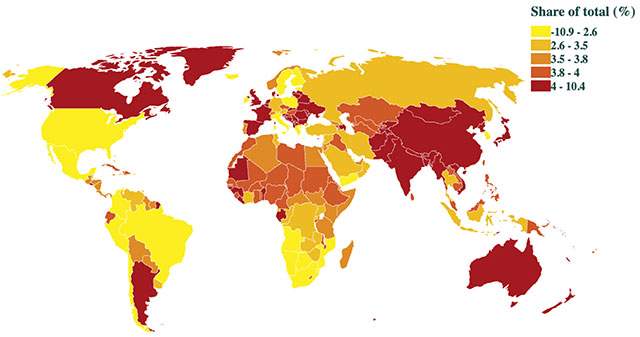

The root of the problem is that our tax code is based on a fiction—the idea that investment gains aren’t income until the underlying investments are sold. Yet that economic income is what keeps adding zeros to the asset balances of the ultrarich. The explosive growth of those untaxed assets over four decades has resulted in a US wealth distribution more extreme, for example, than countries such as Pakistan and Democratic Republic of the Congo.

World Inequality Database

To visualize America’s extraordinary wealth concentration, consider the richest 0.01 percent of US households—the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent. It’s really within this miniscule group, not even the entire top 1 percent, that the wealth is concentrating. Since the early 1980s, the fortunes of the 0.01 percenters—who today represent just 18,400 households—have increased dramatically, both in size and in their collective share of America’s overall wealth.

Based on data compiled by economists Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Blanchet, and Emmanuel Saez at the University of California-Berkeley, the average household in this rarified group had, in today’s dollars, $71 million at the start of 1982. Today, a little over four decades later, they have $972 million. That amounts to a 6.2 percent annual wealth gain, after taxes and lifestyle expenses, and adjusted for inflation.

Even if the richest 0.01 percent had to relinquish all of what our tax code counts as income, the wealth gap between them and the rest would keep growing.

If all Americans experienced such prosperity, it would be cause for celebration. In fact, millions have either lost ground or have been treading water economically since the early 1980s.

To quantify how the Trump megabill affects the wealthiest households, we can extrapolate from a recent report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. The report indicates that the average annual tax cut for the top .01 percenters amounts to about one-tenth of 1 percent of household wealth. If Congress were to do nothing and allow the sunsetting provisions of Trump’s 2017 tax cuts to expire, the net worth of those families would simply grow at the slightly lower rate of 6.1 percent.

Seen through this lens, the bill is a lose-lose proposition. The United States would either incur hundreds of billions more dollars in annual debt or have to slash health care for poor and middle-class Americans to prevent an almost meaningless reduction in the rate at which the bloated fortunes of the ultrarich are expanding. The other 99.99 percent of US households, per Zucman’s data, have seen their wealth grow at an average inflation-adjusted rate of about 2.7 percent, although families in the bottom 40 percent have practically no wealth, and those in the lowest quintile have negative wealth, Zucman confirms.

This growth-rate discrepancy ensures the continuing concentration of the nation’s wealth at the very top—a near quadrupling, over 43 years, of the share held by the richest 1/10,000 of the population. If things continue like this for another 43 years, a crowd not large enough to fill a Major League Baseball stadium will end up with half of the nation’s wealth.

The longer we fail to address this wildly inegalitarian trend, the worse off we’ll all be, because excessive wealth commands excessive political power. Elon Musk, after contributing more than a quarter-billion dollars to Trump’s campaign, just spent four months making unilateral—and reckless—decisions about the funding and staffing of federal agencies. Further wealth concentration will produce more Elon Musks.

But arresting the rate of hoarding by the ultrarich is impossible under our current tax system. Even if the richest 0.01 percent were forced to relinquish all of what our tax code counts as income, the wealth gap between them and the rest of us would continue to grow. A 70 percent tax on income in excess of $10 million—such high “marginal” rates, common before Ronald Reagan was elected, are now considered radical—would fall even shorter of the mark.

“A minimum tax expressed as a fraction of wealth is the most effective way to address this situation.”

In a recent study, Zucman and three colleagues used anonymized IRS data—never before available—to look at the adjusted gross incomes and income tax payments of the wealthiest 0.01 percent of households. According to the data—from 2019, a fairly typical year—even if those families were charged an income and payroll tax rate of 100 percent, the average inflation-adjusted value of their assets still would have increased by 3.5 percent.

The picture gets even worse with the ultra-ultrawealthy. The Wall Street Journal recently reported, based on Zucman’s analysis, that the top 0.00001 percent, just 19 billionaire households, controls 1.8 percent of the nation’s treasure—starting in September 1982, those billionaires have enjoyed inflation-adjusted wealth gains of nearly 9 percent per year, on average.

Placing a 100 percent income tax on these families would merely reduce their average annual growth rate to 7.7 percent—still large enough to ensure, within 28 years, that they would be worth more than $1 trillion per household.

The fiction that paper profits aren’t income created this mess. It allowed Jeff Bezos, for example, to avoid—indefinitely—taxes on more than $200 billion in gains on his Amazon shares. A ProPublica team calculated that Bezos’ effective tax rate from 2014 to 2018 was less than 1 percent of his true income—and also that Bezos, then worth about $18 billion, had even claimed and received a $4,000 child tax credit in 2011 that was intended to help poor and middle-class families. His net worth has grown an average of 20 percent per year—from $30.5 billion in 2014 to about $230 billion today. At this rate, he’ll be a trillionaire by 2033.

Bezos and his ilk can easily micromanage their taxable income by deciding whether and when to sell assets. The income tax, to work as needed, would have to be a tax on economic income, not on some arbitrary figure that oligarchs can control but wage earners cannot. “The super-rich largely avoid the individual income tax, allowing them to have relatively low effective tax rates relative to their wealth,” Zucman told me via email. “A minimum tax expressed as a fraction of wealth is the most effective way to address this situation.”

So far, anyway, Congress has refused to pass a tax on excessive wealth, despite numerous recent proposals. Indeed, four decades into a feedback loop of wealth concentration and political meddling by our growing dynastic class has made the odds of ending the cycle appear ever more daunting.

The US public, certainly, is eager for redistributive tax policies that favor working Americans over the ultrawealthy. That much is evident in the popularity of once-fringe politicians like Sen. Bernie Sanders, the surprise victory of a democratic socialist in the New York City mayoral primary, and the fact that the One Big Beautiful Bill polls very poorly—and extremely poorly, even among Republicans, once people learn how it affects the finances of rich and poor household.

And the cycle has to end. If our lawmakers continue acting as they have, America’s “shared” economic prosperity may soon mirror what we see in the poorest, least developed countries: a tiny, powerful upper class; a small, struggling middle class; and a vast underclass that can barely afford food and shelter.

We’re not quite there yet. But the clock is ticking.

Bob Lord, a tax attorney and associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, serves as senior vice president for tax policy at Patriotic Millionaires

This post has been syndicated from Mother Jones, where it was published under this address.