Today, September 1, 2025, more than 250 media outlets around the world are participating in a unique global protest against the unlawful killing of journalists in Gaza.

At least 210 journalists have been killed since the military operation began, with increasing, incontrovertible evidence of them being deliberately targeted. The action, jointly organised by Reporters Sans Frontieres, the International Federation of Journalists and Avaaz has asked media organisations to share the same common message:

“At the rate journalists are being killed in Gaza by the Israeli army, there will soon be no one left to keep you informed.”

The outlets taking part include The Independent in the UK and NPR in the US as well as media organisations in Europe, the Middle East – including Israel’s brilliant +972 magazine and Local Call – Asia and South America.

“This is not only a war on Gaza, it is a war on journalism itself.” Thibaut Bruttin, the director general of RSF.

This is the best front page I’ve seen so far from Lebanon’s L’Orient – Le Jour:

Huge Kudos to RSF, IFJ and Avaaz for managing to coordinate this. Getting news organisations to agree to anything is almost impossible and it’s heartening to see so many come together. In my last newsletter, I railed against the lack of international solidarity for journalists in Gaza after the last ‘double tap’ strike on a hospital that had seen five journalists murdered. (Though the latest evidence from BBC Verify shows that the hospital was struck not twice but four times. The government of Israel claims the strike was an accident.)

I’m one of more than 1,300 international journalists to have signed a petition demanding access for reporters to Gaza, but it’s not nearly nearly enough.

Though that statement puts what is happening in Gaza into its broader context. This is about much more, even, than the atrocities of what is happening on the ground in Gaza. It really is about the survival of journalism itself. The written and unwritten rules of the international order have privileged and protected the work of journalists. The collapse of these endangers not just journalists reporting in every other country in the world, but all of us. With no witness, no watchdogs, there are no checks on power:

What’s happening in Gaza today reveals a far broader crisis: the erosion of press freedom as a pillar of democracy. The people most directly affected are not only the millions of civilians in Gaza enduring war beyond public scrutiny, but also global citizens everywhere whose right to receive free and independent information is being denied.

If this press blackout continues, it sets a dangerous precedent: that governments and military actors, through censorship, obstruction, and force, can shut down access to truth in times of war. This is the very playbook of authoritarianism: control the narrative, silence independent voices, and sever the link between reality and public understanding. To defend press access in Gaza is to defend the democratic ideal that truth is not the property of the powerful.

As someone who for years was smeared as “an activist” rather than a journalist, I especially appreciated this sentence at the bottom of the statement:

“This is not activism. It is journalism, and it is urgent.”

(I made peace with being both a journalist and an activist years ago, btw. I’m proud to say that I’m an activist for the truth.)

The petition did have some sort of impact. It was followed by a joint statement on behalf of 27 countries – including the UK – stating that Israel should allow international journalists access.

Though that statement also underlines the hypocrisy of these goverments’ positions. The UK government joined that call, while still selling military equipment to Israel. It’s done nothing to back that call with action. No pressure has been brought to bear.

The attacks on journalists, the silence of the world, the complicity of the US and UK governments is a harbinger of what is to come. We’ve seen how the authoritarian playbook works. How the flouting of international rules and norms in one country is quickly aped and copied by authoritarians in other countries. It’s why what is happening in Gaza sets a wholly chilling new precedent. The world has never seen the systematic murder of journalists on anything like this scale. Nor have the technological means previously been available.

A chilling investigation by Yuval Abraham of +972 magazine revealed the existence of a ‘legitimisation cell’ inside the IDF tasked, among other things, with ‘identifying Gaza-based journalists it could portray as undercover Hamas operatives, in an effort to blunt growing global outrage over Israel’s killing of reporters’. A previous investigation by the same outlet documented how AI was being used to profile and surveille targets for assassination creating automated ‘kill lists’.

And it’s not just weapons. The entire population of Gaza is being deliberately starved. (See this report by the Guardian’s brilliant Emma Graham-Harrison on the ‘Mathematics of Starvation’.) That includes journalists. AFP, BBC, AP and Reuters have all said their own journalists face starvation:

“For many months, these independent journalists have been the world’s eyes and ears on the ground in Gaza. They are now facing the same dire circumstances as those they are covering.”

Who’s not taking part

If you’re scrolling English language social media today, you’ll see posts from American Prospect, Zeteo, the Columbia Review of Journalism, Byline Times, Al Jazeera, Ireland’s The Journal, UK Press Gazette, Rappler in the Philippines, and New Zealand’s Stuff magazine as well as the 200+ foreign-language press and the outlets named above. You’ll perhaps see posts from brilliant outspoken journalists like Alex Crawford from Sky News. And there is even, finally, an op-ed from the New York Times.

But the NYT is not blacking out its front page. Nor are the vast majority of ‘mainstream’ news organisations. I’d urge you today to pay special attention to who’s not joining in. And if you read or subscribe to those newspapers – including my former employers at the Guardian and Observer – I’d urge you to ask them why.

Why are they ‘sitting this one out’? Why aren’t they joining their colleagues from around the world? Why not show collective solidarity?

All mainstream outlets rely on correspondents and stringers operating in Gaza. All available evidence suggests those reporters are on a death list. Why on earth would any editor boycott an international campaign of solidarity and support? Why aren’t their political correspondents asking the prime minister this at press conferences? Why are they still running interference for ministers taking these decisions?

I understand that there are efforts behind the scenes by individual western outlets to exfiltrate their correspondents from Gaza. That they are doing so is to seemingly to acknowledge that there is no safe way to report on what is happening there. So, why not say so? Why not qualify statements from Israeli government sources with that information?

Two weeks ago, the Columbia Review of Journalism (based at the school that’s home to the Pulitzers) published a bunch of opinions on the subject of what more international journalists and outlets could be doing and I’m going to re-publish extracts from them here.

This first by Youmna ElSayed, Al Jazeera’s Gaza Strip correspondent, now living in Cairo. It’s a trenchant pushback against even these calls for international press to enter.

Push on the ground

Journalists can find alternate routes to push to enter. If they tried to enter through the Rafah border, when it was open, they would have gotten in. The reality is that no international organization is willing to send its foreign journalists into Gaza, because after they conduct the risk assessments, they realize there is no ability to actually guarantee any kind of protection, because there isn’t any place that is safe.[…]

The fact that news organizations are not willing to take the risk to enter Gaza is an implicit acknowledgment of the reality that it isn’t a safe place to be and that journalists are not protected there—and yet those same news organizations are not acknowledging that reality directly, openly, and reporting about the way it is.

Beyond newsrooms, press freedom organizations have the ability to place governmental pressure, international pressure to impose sanctions of some kind on Israel. We need to see something other than verbal condemnation. We’ve passed the point of verbal condemnation. We’ve passed the point where we have reports and we’ve documented this.

Mohammed El-Kurd, a Palestinian writer, suggests:

…a march toward the Rafah border—if two hundred, three hundred journalists just went to Egypt and walked toward the crossing. Even if it were stopped by the Egyptian forces, that would be a news item and drive massive attention.

Echoed by Nader Ihmoud:

Bring in the most influential Western journalists—an Anderson Cooper, a Wolf Blitzer—along with some politicians. Put some bodies on the line that Israel would be afraid to attack.

Sharif Abdel Kouddous, the Middle East and North Africa editor of Drop Site News, puts responsibility not just on the outlets but individual journalists too:

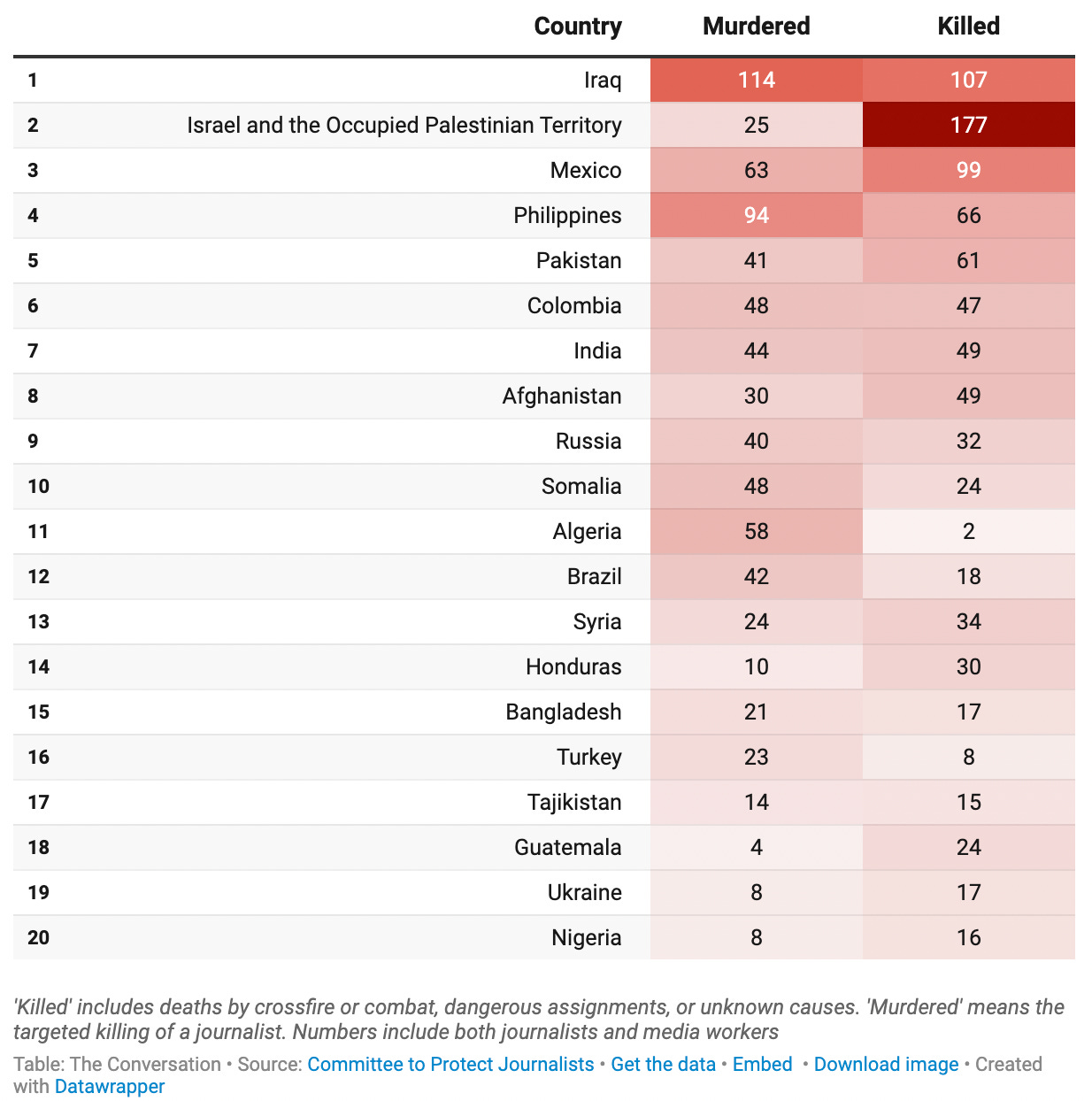

Journalists in Western newsrooms could strike. They could refuse to work until some sort of substantive demand for a policy change at these institutions is fulfilled. Perhaps a disclaimer at the bottom, or within, every article that quotes Israeli authorities that Israel has killed far more journalists in Gaza than anywhere in the world since the Committee to Protect Journalists started keeping records, and therefore the veracity of any statement is dubious.

There are other excellent suggestions, including one from Kenneth Roth, the former head of Human Rights Watch for three decades, urging the International Criminal Court prosecutor to file war crime charges explicitly about Israel’s killing of journalists.

There’s one positive takeaway from the list: the suggestion by documentary maker, Hind Hassan, that global media outlets should observe a ‘global blackout’.

Well, some of them did.

The Final Call?

Final words from Mohammed Asad, a journalist inside Gaza. He issues a ‘final call’ for international journalists to pressure their governments to allow them to come to Gaza.

Study his face. The last journalist I saw issuing such an appeal – Maryam Abu Daqqa – is now dead.

I’m going to publish a ‘Part 2’ on this tomorrow. If you have thoughts, please do add them to the comments. I’m interested to hear your views. With thanks as ever, Carole

A note on what I’m doing and why. I’m an investigative journalist who worked for the Guardian for 20 years latterly investigating the intersection of politics and technology that included 2018’s exposé of the Cambridge Analytica/Facebook scandal. The opaque and unaccountable Silicon Valley companies that facilitated both Brexit and Trump are now key players in an accelerating global axis of autocracy. I believe this is a new form and type of power that I’m committed to keep on exposing: Broligarchy.

This post has been syndicated from How to Survive the Broligarchy, where it was published under this address.