On an April episode of the popular Politics War Room podcast, the veteran journalist Al Hunt posed an increasingly common question from listeners to Democratic strategist James Carville. “Is Trump looking to spark enough protest to justify declaring martial law in 2026, thus suspending the election?” Hunt asked.

“You’re so correct to be concerned about this,” Carville responded. “It’s getting worse by the day. It is not going to stop getting worse. And I would be—we ought to be—on high, high alert.”

Such chatter is widespread these days among Trump’s opponents—and with good reason. Trump is the most openly authoritarian president in US history and has already incited an insurrection in an attempt to remain in office.

The good news, according to experts, is that Trump doesn’t have the power to unilaterally cancel the midterms. The states, with oversight from Congress, run their elections. Voting will go forward whether Trump likes it or not.

Cleta Mitchell, a former Trump lawyer who helped the president attempt to overturn the 2020 election, ominously predicted that Trump would “exercise some emergency powers to protect the federal elections going forward.”

But there are still many reasons to be concerned about the rapidly escalating threats to America’s election system. Given Trump’s extreme assertions of executive power, the autocratic nature of his second term, and the stacking of his administration with hardline loyalists, many of the outlandish schemes he considered to stay in power in 2020—such as using the military to seize voting machines in battleground states—don’t seem as far-fetched today. And his deployment of the National Guard and Marines in response to protests against ICE in Los Angeles, which was followed by a similar federal takeover of Washington, DC, has heightened fears about how far Trump will go to keep his party in control of Washington. “The California events really rattled a lot of people,” says Sophia Lin Lakin, director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project.

The scale of Trump’s interference in the midterms has become crystal clear in recent weeks. The president pressured Texas to pass a mid-decade redistricting plan last month that would add five more Republican seats in the US House. Shortly thereafter, he vowed to “get rid of MAIL-IN BALLOTS” and “Seriously Controversial VOTING MACHINES,” through an executive order. “If we do these TWO things,” he wrote on Truth Social, “we will pick up 100 more seats.”

The stakes for the midterms are incredibly high. It’s the last chance for Democrats to hold Trump accountable at the national level before he leaves office (unless he attempts to follow through on his musings to seek an unconstitutional third term). At the same time, nearly 100 state-level races for offices like governor, secretary of state, and attorney general are on the ballot, which will determine who’s in charge of supervising elections in 2028.

But unlike 2018, when Trump was still a political novice, or 2022, when Democrats controlled the presidency and Congress, the 2026 midterms will take place under a radicalized Trump administration that appears hellbent on crushing its opposition. “Our elections have faced an elevated level of risk for some time and now there’s one additional factor that’s going to exacerbate all the other risks, which is a weaponized federal government that might be deployed in ways that can disrupt or interfere in free and fair elections,” says Wendy Weiser of the Brennan Center for Justice. “That’s a dramatic new factor this year.”

Here are 10 ways Trump and his allies are tilting the midterms in their favor before anyone has cast a vote.

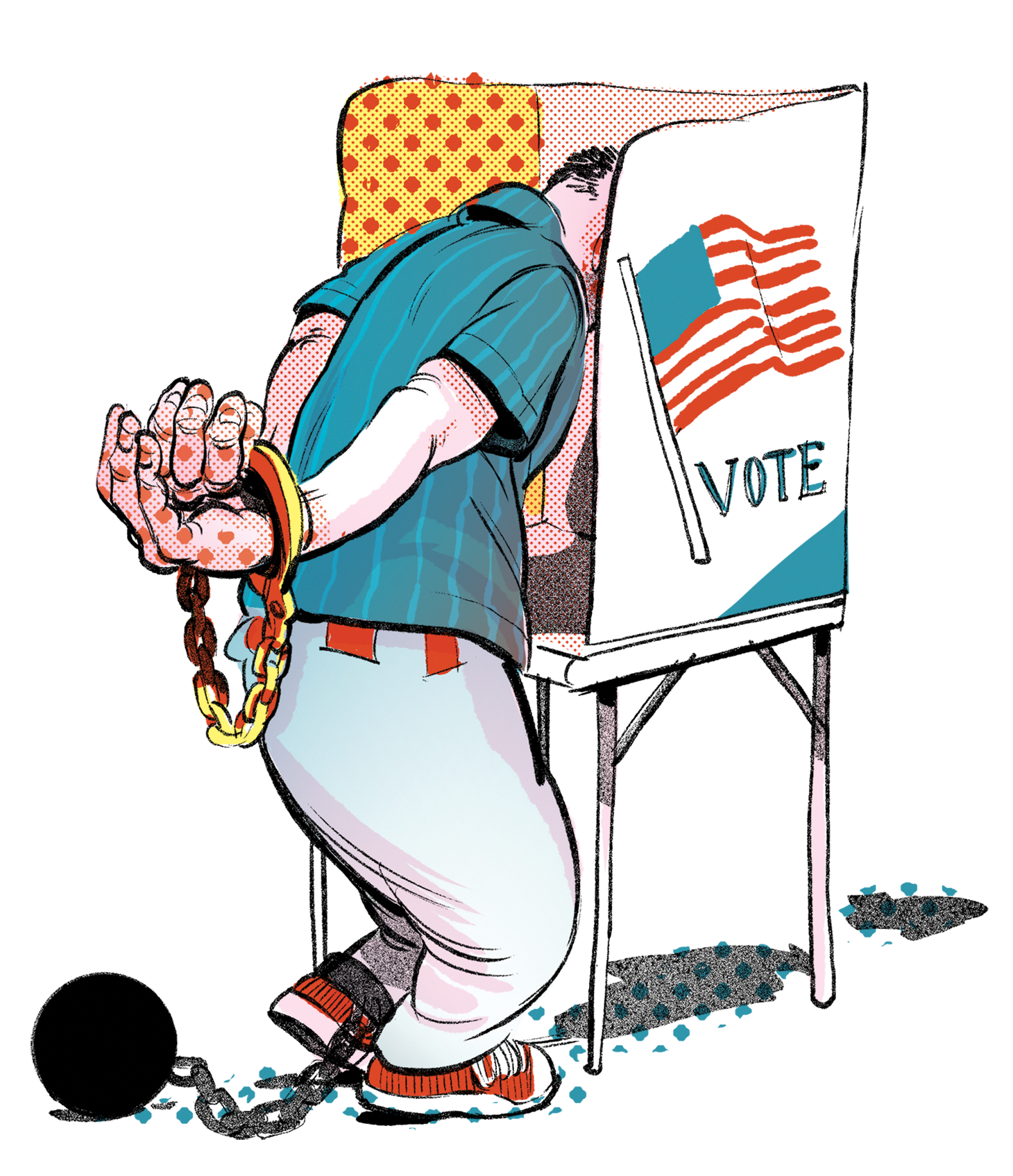

Nationalizing Voter Suppression

In March, Trump signed a far-reaching executive order that would upend how Americans register to vote, how they cast their ballots, and how their votes are counted. The voting rights group Fair Fight called it a “MAGA fever dream.” The laundry list of suppressive policies included requiring proof of citizenship, such as a passport or birth certificate, to register to vote in federal elections; specifying that mail-in ballots must be received by Election Day or else states will lose federal funding or face lawsuits from the Justice Department; and giving DOGE and the Department of Homeland Security the power to sift through federal immigration databases and subpoena state voting records to search for alleged voter fraud.

Much of the order has been blocked in court—at least for now. But that has only mitigated part of the threat.

States are already adopting similar policies. And Trump could blame “crazy radical left” judges in a bid to contest the midterm results as fraudulent. Indeed, much of the order appears designed to undercut the legitimacy of election outcomes.

Voting rights groups are particularly worried about a little-noticed section that calls on the Election Assistance Commission to “rescind all previous certifications of voting equipment based on prior standards.” It specifies that states should adopt technology that is not currently available on the market, putting them in a seeming catch-22—required to use voting machines that they can’t get. If those machines are not certified, Trump might try to resurrect his 2020 plan to seize them, experts warn. “The executive order lays fresh groundwork for an attack on the outcome of elections that involves claims of compromised or errant voting machinery,” writes Bob Bauer, who served as White House counsel under Barack Obama.

In June, Trump called for a special prosecutor to investigate the 2020 election, which could embolden such nefarious efforts and elevate fringe conspiracy theories. He issued his latest threat to ban mail ballots and outlaw voting machines after meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, who he claimed told him, “Your election was rigged because you have mail-in voting.”

The president’s lies about voting have already been used to justify sweeping assertions of executive authority. After the nationwide No Kings protests on June 14, Trump called for ICE to target “America’s largest cities,” which he dubbed “the core of the Democrat Power Center…where they use Illegal Aliens to expand their Voter Base [and] cheat in Elections.”

Advocates also worry that Trump’s mass deportation agenda could evolve into a vast election policing apparatus deployed against his political opponents. That could include the president federalizing the National Guard (like in Los Angeles and Washington, DC) and ordering the military to patrol the polls, demanding citizenship checks at polling stations, authorizing ICE raids in Democratic areas in the runup to the election, and arresting political leaders who don’t comply with his policies.

“They’re petrified over at MSNBC and CNN that, hey, since we’re taking control of the cities, there’s going to be ICE officers near polling places,” former Trump advisor Steve Bannon said on a recent podcast. “You’re damn right.”

Cleta Mitchell, a former Trump lawyer who helped the president attempt to overturn the 2020 election and now leads a national network of election deniers, also predicted on a podcast in early September that Trump would “exercise some emergency powers to protect the federal elections going forward.” Mitchell told former US Rep. Jody Hice that “the chief executive’s authority is limited in his role with regard to elections except where there is a threat to the national sovereignty of the United States, as I think that we can establish with the porous system that we have.”

These comments have to be taken seriously given the disdain that Trump and his allies have shown toward the democratic norms, rules, and even court rulings.

“The thing I learned on January 6 was that election deniers don’t have to change the laws or the policies,” says Hannah Fried, executive director of All Voting Is Local, a pro-democracy group. “They will take what they want by any means.”

Silencing His Enemies

Two weeks after the 2020 election, Trump fired Chris Krebs, the director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, after he tweeted an interagency statement declaring the November contest “the most secure in American history.” But the attacks on Krebs didn’t stop there. Trump issued an executive order in April 2025 stripping Krebs of his security clearance for having “falsely and baselessly denied that the 2020 election was rigged and stolen.” Because Trump also called on federal agencies to “suspend” any security clearances held by Krebs’ associates, Krebs decided to resign from his job as chief intelligence and public policy officer at SentinelOne, a cybersecurity company worth $5 billion. “It’s about the government pulling its levers to punish dissent,” Krebs told the Wall Street Journal.

The retribution against Krebs was hardly a one-off. In March, Trump issued an executive order against the law firm Perkins Coie because of its affiliations with the likes of Hillary Clinton and George Soros. That same month, he rescinded the security clearance of lawyer Mark Zaid, who represented an intelligence community whistleblower who exposed Trump’s attempt to pressure Ukraine to interfere in the 2020 election, which led to the president’s first impeachment.

“The thing I learned on January 6 was that election deniers don’t have to change the laws or the policies. “They will take what they want by any means.”

Many of these actions function as a form of election interference. Trump issued an executive order on April 24 accusing ActBlue, which has raised $16 billion for Democratic candidates and causes since its founding in 2004, of accepting illegal foreign contributions and straw donations, ordering Attorney General Pam Bondi to complete an investigation within 180 days. ActBlue called it “Trump’s latest front in his campaign to stamp out all political, electoral and ideological opposition.”

As the midterms approach, it’s not hard to imagine administration officials ramping up plans to expand investigations into groups they view as a threat, including pro-democracy organizations, voter registration efforts, and get-out-the-vote initiatives.

“The targeting of individuals and groups, using the unique law enforcement powers of the federal government, can really be devastating,” says Weiser. “Even if they’re unlawful, and even if you win, there’s so much damage that that could cause, as a method of control or intimidation or retaliatory punishment against people involved in the elections process.”

Dismantling Efforts to Prevent Election Interference

Trump didn’t just fire Krebs and target him via executive order. He’s systematically dismantling the agency Krebs once led, CISA, significantly increasing the likelihood that foreign and domestic actors could meddle in US elections.

Shortly after Trump took office, the administration announced it would “pause all elections security activities” at the agency. It placed staffers on administrative leave and stripped funding from systems that alert state and local governments to cybersecurity and election threats. Trump’s budget proposal would cut nearly $500 million from CISA and eliminate the agency’s work on countering misinformation and disinformation. Separately, Bondi disbanded an FBI task force charged with combating foreign election interference by the likes of Russia, China, Iran, and other countries.

CISA has seen an exodus of career professionals replaced by Trump loyalists. Roughly 1,000 people have already left the agency, cutting its workforce by a third. Its new director of public affairs, Marci McCarthy, is a former Republican Party official in Georgia who has questioned the integrity of the 2020 election and claimed that January 6 was “set up and orchestrated by the FBI.”

Trump famously called on Russia to hack into Hillary Clinton’s emails during the 2016 campaign, then called evidence of Russian interference “a hoax.” Voting rights experts worry that his administration’s unwillingness to stop election interference could lead to a range of catastrophic outcomes, such as foreign or domestic actors accessing voting machine equipment, breaching state voter rolls, or attacking power grids or other critical infrastructure. In 2024, for example, bomb threats were called into polling places in largely Democratic counties in at least five battleground states.

“The idea that we would unilaterally disarm our intelligence capabilities when the world is far more dangerous and more contentious and the role of the United States in the world is being challenged far more than in 2017 and yet we have far less capabilities aimed at protecting our elections, it’s madness,” says Alexandra Chandler, a military intelligence analyst for more than a decade who now serves as director of the elections program at Protect Democracy.

Targeting Democratic Officials

When Trump allies in the DOJ charged Rep. LaMonica McIver for clashing with ICE agents during the arrest of Newark Mayor Ras Baraka outside an ICE detention center, it represented a dangerous escalation of Trump’s weaponization of law enforcement. Congressional historians had to go back to 1799 to find an example of a sitting House member facing a similar felony charge.

Many public officials have been threatened with jail time, and since April, at least five have been arrested or detained.

It’s a tactic that’s already been used in high-profile political situations. The administration overruled career prosecutors to drop corruption charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams, which one now ex-prosecutor said amounted to a quid pro quo to persuade the mayor to support Trump’s mass deportation program. The Justice Department subsequently announced an investigation of Adams’ then-leading opponent, Democratic mayoral candidate Andrew Cuomo, a month before the election. ICE agents also arrested Democratic mayoral candidate Brad Lander a week before the primary as he was escorting a migrant out of a New York City court. Lander held onto the migrant and demanded to see a judicial warrant as federal agents moved to detain the man.

While law enforcement officials target Trump’s political opponents, the president has increased the risks of election interference and political violence by granting clemency to more than 1,500 insurrectionists, including the far-right Oath Keepers and Proud Boys. “It raises the specter of the abuse of criminal law, but it also raises the specter of using the immunity power and the pardon power to try to encourage other people to engage in wrongdoing in what might be blatant or even less centrally coordinated ways of trying to interfere in the election,” says Weiser. “That green light can unleash all sorts of wrongdoing and interference in the election.”

Weaponizing the Justice Department

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the DOJ is the nerve center of Trump’s attempt to weaponize the federal government for his own ends.

In the runup to the midterms, the department will likely undertake high-profile investigations into alleged voter fraud and lean on states to adopt restrictive policies that could include removing eligible voters from the rolls, challenging mail-in ballots, and targeting Democratic election officials. Indeed, Project 2025—the infamous conservative blueprint for the second Trump administration—went so far as to call on the department to use one of the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan Acts to prosecute election officials who issue guidance Republicans disagree with. That would be a complete perversion of a law that was passed to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people, including their right to vote. The DOJ is now reportedly considering bringing criminal charges against election officials if they do not safeguard their voting systems to the administration’s satisfaction.

Trump political appointees removed all the senior managers in the Justice Department’s voting section and ordered the dismissal of every major active case.

The department’s transformation in the first six months of Trump’s administration has been astonishing. Most notable is Trump’s evisceration of the DOJ’s civil rights division, which has historically been known as its “crown jewel.”

Trump appointed Harmeet Dhillon, a loyalist with a long history of attacking voting rights, as head of the division. She subsequently gutted the division’s staff and completely changed its priorities.

Around 250 lawyers, 70 percent of its total, have left the civil rights division since January, and the department’s voting section, which enforces the Voting Rights Act and other voting rights laws, has shrunk from 30 lawyers to just a handful. Political appointees removed all the senior managers in the voting section and ordered the dismissal of every major active case, including litigation challenging restrictive voting laws and gerrymandered maps in states such as Arizona, Georgia, and Texas.

At the same time, Dhillon omitted the longtime mandate of stopping racial discrimination in voting from the section’s mission statement and instead pledged to address Trump-inspired priorities that include enforcing the president’s executive order on elections and “preventing illegal voting, fraud, and other forms of malfeasance and error.” Under her leadership, the civil rights division has been turned on its head, with voting statutes now deployed as a means of making it harder to vote.

In its first major voting-related lawsuit, Trump’s DOJ sued the state of North Carolina over its voter rolls, which could potentially lead to thousands of eligible voters being wrongly purged before the midterms. It has demanded copies of voter registrations lists from more than 20 states and has asked Colorado to preserve its records from the 2020 election and turn over all documents related to 2024—a sweeping and unprecedented request that could be used to support jailed election denier Tina Peters, the former Mesa County clerk serving a nine-year sentence for giving access to sensitive voting equipment to election conspiracists. In recent months, the administration has also sought access to voting equipment in Colorado and Missouri, but were rebuffed by county election officials.

Dhillon has gotten directly involved with Trump’s mid-decade gerrymandering effort. She sent a letter to Texas in early July alleging that four of the state’s congressional districts, which were all represented by Black or Hispanic Democrats, were “unconstitutional racial gerrymanders.” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott then cited that letter as the reason why the state’s congressional map needed to be redrawn.

The acting head of the voting section, Maureen Riordan, recently served as counsel to a conservative group, the Public Interest Legal Foundation, that has made outlandish claims about voter fraud, supported restrictive voting laws, and helped Republicans gerrymander local areas. The group was part of a right-wing legal onslaught challenging voting laws across the country in advance of the 2024 election.

The North Carolina Model for Overturning Elections

It was no coincidence that the first voting-related lawsuit filed by the Trump Justice Department, in North Carolina, amplified claims raised by a Republican judicial candidate who spent six months trying to overturn the victory of his Democratic opponent.

Despite two recounts affirming the 734-vote victory of Democratic North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Allison Riggs, Republican Jefferson Griffin refused to concede and challenged the eligibility of more than 65,000 voters, citing zero evidence of wrongdoing.

Like Trump in 2020, Judge Griffin primarily challenged certain voting methods that were more likely to be used by Democrats—ballots cast by mail and during early voting. He found no instances of illegal voting but, like Trump, attempted to change the laws after the election to retroactively alter the outcome.

And, like Trump, he cherry-picked where he was contesting ballots, seeking to invalidate military and overseas votes only in six heavily Democratic counties.

Unlike Trump, Griffin nearly succeeded in overturning the election, thanks to the GOP-dominated state court of appeals and state Supreme Court greenlighting his scheme to throw out enough votes to potentially reverse Riggs’ win. It was only after a Trump-nominated federal judge ordered the state board of elections to certify the election that Griffin conceded.

It’s a blueprint that other losing Republicans are likely to follow. “It was a win for free and fair elections but such a warning,” says Chandler.

Just as Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 election inspired election deniers to seize positions of power across the country, Griffin’s success in state court could help normalize election subversion, especially in states where Republicans have partisan allies on courts and election boards. And now, if a similar lawsuit is filed, the federal government could very well weigh in on the side of those seeking to overturn the election.

“I can see the federal government, sadly, as a partner, zooming down into the state level, where needed, to say, this race, this race, this race, the federal government is here as a validator and legitimizer of these efforts to say this election was not free and fair or this election is not legitimate,” says Chandler.

State-Level Voter Suppression and Election Subversion

The same day Griffin conceded, Republicans won an arguably bigger but lesser-noticed victory, taking control of North Carolina’s board of elections, which will allow them to set voting rules and oversee election certification in this key battleground state.

Republicans accomplished this feat by convening a lame-duck session two weeks after the November 2024 election, for the ostensible purpose of passing a hurricane relief bill. With no public notice, they blindsided Democrats by stripping the state’s incoming Democratic governor, Josh Stein, of the power to appoint a majority of members on the state election board and 100 county election boards. The legislature transferred that authority to the Republican state auditor, Dave Boliek, who had no experience overseeing elections.

The Republican majority appointed by Boliek is stacked with hardliners: Its new chair, Francis De Luca, is former president of the right-wing Civitas Institute, which for years has spread unfounded claims of voter fraud, supported cutting back on voting access, and filed litigation challenging election outcomes. Another member, former gop state Sen. Bob Rucho, was an author of a notorious pro-Republican gerrymander. At the board’s first meeting, the new GOP majority fired the board’s well-respected executive director and replaced her with the counsel to the GOP speaker of the North Carolina House.

These appointments will have major ramifications. The state board administers elections and issues guidance to county officials, who in turn have the power to decide the timing and location of early voting. Both the county and state boards must certify election outcomes. That raises the possibility that Republicans will cut back on voting access and refuse to certify results should a Democrat narrowly win—the very thing that Griffin sought to do in the contested state Supreme Court race. The risk of election subversion isn’t confined to North Carolina. Twenty-four election deniers in 18 states hold a statewide office with election oversight duties, according to States United Action, a nonpartisan voting rights group, raising fears that they could use their power to undermine fair election administration. All Voting Is Local found that the number of counties in eight battleground states “facing significant threats of election sabotage” increased from 87 in 2022 to 117 in 2024.

In addition, Republicans have continued their decades-long push to limit access to the ballot, which intensified dramatically following Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election. Thirty-five new laws were passed in 19 states in the first eight months of this year that will restrict voting access or impede fair election administration, according to the Voting Rights Lab.

Trump-Dominated Courts Gutting Voting Rights

The Justice Department’s abandonment of voting rights enforcement is particularly devastating given the extreme decisions coming from Trump-friendly judges on lower courts. The federal courts may have thwarted Trump’s attempt to steal the 2020 election, but they are helping Republicans in other key ways.

In 2023, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals upended decades of precedent by holding that private plaintiffs could not bring lawsuits to enforce Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the key remaining provision of the law. The court said that only the US attorney general could file such cases, even though more than 80 percent of successful Section 2 lawsuits have been brought by private plaintiffs, typically individual voters represented by groups like the ACLU and NAACP.

Republicans are turbo-charging efforts to give their party a new gerrymandering edge in 2026.

Given the Trump administration’s fervent opposition to the Voting Rights Act, this means that enforcement of the law has come to a standstill in the seven states in the Midwest and Great Plains that fall under the 8th Circuit’s jurisdiction. That has already led to the loss of representation for Black voters in Arkansas and Native Americans in North Dakota who challenged gerrymandered maps.

If the Supreme Court, which has repeatedly gutted the Voting Rights Act, were to find that the 8th Circuit’s decision applied nationwide, it would deal a death blow to the remaining provisions of the law. The court recently paused the 8th Circuit’s decision as it determines whether to hear the case.

But the Voting Rights Act remains firmly in the crosshairs of the conservative justices. In early August, the court announced new legal briefings in a Louisiana redistricting case to decide “whether the state’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.”

That raises the prospect that the court’s conservative majority could rule before the midterms that districts drawn to comply with the VRA that give people of color the opportunity to elect their preferred candidates may be unconstitutional, which would all-but-destroy the remaining protections of the law. “They’re trying to take away the last tool the Supreme Court has not fully dissolved to stop the gross manipulation of elections,” says Janai Nelson, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

That’s not the only way that courts dominated by Republican appointees have sought to pave the way for radical decisions. Days before the 2024 election, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a Mississippi law that allowed for mail-in ballots to be counted if they were postmarked by Election Day and arrived within five business days following the election. Much like Trump’s executive order, the court held, in a lawsuit filed by the Republican National Committee, that those ballots must arrive by Election Day instead. Mississippi has appealed the ruling, but if the Supreme Court sides with the 5th Circuit, that would upend mail-in voting deadlines for millions of voters in 17 states with similar laws.

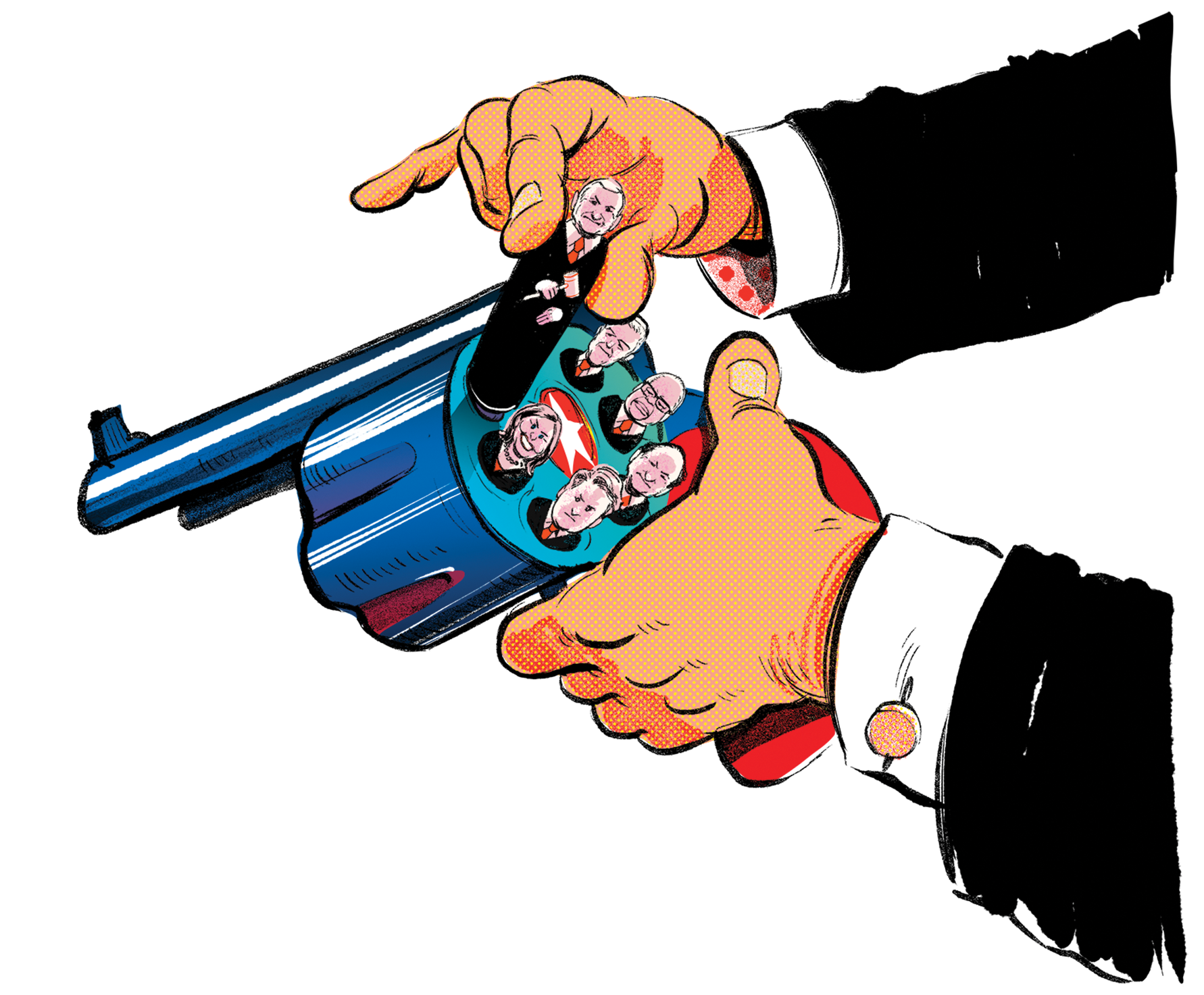

Re-Gerrymandering the States

If efforts to tilt the country’s voting laws toward Republicans prove unsuccessful, the GOP has a backup plan: use gerrymandering to predetermine election outcomes.

That effort proved successful in 2024, when heavily skewed new maps drawn by North Carolina Republicans allowed the party to pick up three US House seats in the state. If Democrats had held on to those seats, they would have won control of the chamber.

Now Republicans are turbo-charging efforts to give their party a new gerrymandering edge in 2026. It began this summer, when Texas Republicans—following intense pressure from the Trump administration and dubious legal arguments from the DOJ—announced they would redraw their US House districts in advance of the midterms. Texas is already one of the most gerrymandered states in the country, and districts are typically remapped only at the beginning of the decade, following the decennial census. But the administration urged state Republicans to adopt an even more “ruthless” approach that could allow the GOP to win as many as five additional seats and prevent Democrats from retaking the House.

The White House is now aggressively lobbying other Republican-controlled states to follow suit. On Trump’s orders, Missouri Republicans began a special legislative session on September 3 to pass a new redistricting map that would eliminate one of two Democratic districts in the state, giving Republicans 90 percent of the state’s US House seats. Indiana and Florida are facing under similar pressure to do the same.

Ohio is already set to redraw its congressional districts by the end of the year. During the post-2020 redistricting cycle, Ohio Republicans drew maps for the state legislature and US House that the state Supreme Court struck down seven times, but that nonetheless remained in effect for the 2022 elections, giving Republicans a 10–5 advantage in the state’s US House delegation. Because the maps did not have bipartisan support, the GOP-controlled Ohio legislature will have to draw new US House districts for the 2026 midterms, which could net Republicans up to three more seats.

Blue states, including California, have vowed to retaliate with their own mid-decade redistricting plans, but Democrats remain at a distinct disadvantage in a gerrymandering arms race, because Republicans control more states and have fewer constraints on partisan gerrymandering.

Blocking Election Certification

Imagine this scenario: control of the House isn’t called on election night 2026. The balance of power depends on one or more close races in California, which can take weeks to count votes. Trump alleges widespread fraud, making spurious claims about post-election “vote dumps” and noncitizens voting. The president pressures Speaker of the House Mike Johnson—who voted against certifying the electoral votes from Arizona and Pennsylvania in 2020 and supported a lawsuit to overturn that presidential election in four battleground states—not to seat any Democrats in disputed elections. The speaker persuades the House, while it is still under GOP control before the next speaker is chosen, to block members of California’s delegation, plunging the body into chaos.

While that scenario may sound implausible, it’s not impossible. More than 600 elections have been contested in the House since 1789, including half a dozen since 2000. Losing House candidates can challenge their election under the Federal Contested Elections Act of 1969, and a member can contest the right of another to be sworn in. Each chamber of Congress has the authority to adjudicate election disputes.

There were frequent skirmishes over the seating of members of Congress during the early years of the country. In the volatile period after the Civil War, when Reconstruction was violently overthrown and Jim Crow established in the South, white members of Congress repeatedly overturned the elections of Black members. The first Black man ever elected to the US House, John Willis Menard of Louisiana, was never seated in 1869 after his white opponent contested his election. Similarly, Josiah Walls, the first Black man elected to represent Florida in the House, was unseated twice by his colleagues during election challenges in the 1870s.

This shameful history is newly relevant today, given the lengths Republicans have gone to block the certification of elections at the state and federal level during the Trump era. Johnson and his allies could attempt to prevent or override state-level certification of a member and declare their own winner. “If it’s a closer election, where one member is dispositive, I would certainly be concerned about it,” says Joaquin Gonzalez, a veteran voting rights lawyer in Texas who has extensively studied this issue.

The sheer volume of threats to democracy can feel so overwhelming that some people may choose not to vote for fear that their ballot will not matter. And that may be part of Trump’s plan. Research by the States United Democracy Center found that Americans were more likely to turn out in 2024 if they felt confident their vote would count.

But there is also a broad coalition of lawyers, pro-democracy groups, election officials, and state leaders preparing to fight back, whether in the courtroom, at the ballot box, or on the streets.

“There’s a role here for litigation,” says All Voting Is Local’s Fried. “There’s a role here for communities—to show up to their board of elections meetings and in front of their state legislatures and demand their right to vote. There’s a very important role for elections officials.”

The decentralized nature of the US election system makes it harder to interfere in one pivotal state or race. And pro-democracy groups have already brought together a wide range of public policy officials to simulate many of the worst-case scenarios Trump floated in 2020 and 2024, making them more prepared to face this current authoritarian moment.

“There are all these levers and all of these tools to interfere with, sabotage, subvert elections,” says Chandler, “but there are far fewer people that are going to be surprised now, and that’s the good thing.”

This post has been syndicated from Mother Jones, where it was published under this address.