On July 4th, Mexico City witnessed its first mass mobilization against gentrification. A 2022 agreement between Mexico City’s government, UNESCO, and AirBnb rolled out the welcome mat for hordes of American “digital nomads,” with remote workers effectively colonizing popular neighborhoods and precipitating a monumental housing crisis. On the 4th, Mexico City residents took the streets, eventually shutting down busy intersections and looting high-end retailers over cries of “Gringo go home!”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, of the social-democratic Morena party, condemned the protests as “xenophobic” anti-Americanism. “No one should be able to say ‘any nationality get out of our country’ even over a legitimate problem like gentrification,” she said. We should think twice before accepting the Mexican state’s claims.

“This fight against plundering isn’t about xenophobia (hatred of foreigners). Travelers and migrants aren’t to blame,” announced one of the collectives organizing the march. “It’s the system that imposes inequalities and the nation-states that defend them.”

“Our objective is nothing less than becoming a social movement capable of stopping the machinery of capitalism and improving the quality life for millions of our families,” wrote journalist and organizer Námme Villa del Ángel. Good luck finding this perspective at actually xenophobic anti-immigrant rallies in the US or Europe. There are xenophobic attitudes in Mexico, but resistance to gentrification is not one of them.

On the contrary, the fight against gentrification is a potential point of solidarity between peoples in struggle on both sides of the US-Mexico border. The “digital nomads” gentrifying neighborhoods like Roma and La Condesa in Mexico City are the same people gentrifying Austin and San Francisco and Brooklyn. It’s a small caste of highly-educated, highly-paid workers and owners—predominantly light-skinned citizens of wealthy nations—who are displacing urban communities both in their home countries and abroad. Were mass protests against gentrification in New York, Philadelphia, and Oakland anti-American xenophobia, too?

We are witnessing the emergence of the material basis for transnational solidarity of a new type, one conducted not between national parties but between global cities in struggle against a common foe. As we’ll see, this new type of solidarity was predicted by revolutionaries decades ago. So why is it that, when we think of international solidarity, we’re often left with stodgy leftist parties making grandiose declarations of proletarian brotherhood with one-party states? Why is “international solidarity” stuck in the Cold War? And what can it mean for the 21st century?

A haunting of dead weights

Our current understandings of international solidarity are inherited from the New Left of the 1960s and 70s, when leading radicals turned to Marxism-Leninism amidst the Civil Rights Movement and national liberation struggle in Vietnam.

As Max Elbaum writes in his (highly recommended!) study of the “New Communist Movement,” Revolution in the Air:

“[T]he critique of US policy in the Third World became the entry-way to Marxism for thousands of young radicals… Of all the traditions within Marxism, it was Leninism that placed the most emphasis on the imperialist nature of twentieth-century capitalism, on the revolutionary potential of national liberation struggles, on the legitimacy of armed struggle, and on the primacy of building solidarity with oppressed peoples. ”

In the Marxist-Leninist framework, international solidarity is a relationship between nations, with the revolutionary currents within each nation represented by a single hierarchical vanguard party. New Left communist parties in the United States variously championed the party-states of China, Cuba, or Vietnam as the leading edge of revolution. As the radical leftist Guardian newspaper wrote in 1976, “there can be no communist party – especially in the heartland of US imperialism – that does not base itself on proletarian internationalism.”

The New Communist Movement was plagued by leader-worship and dogmatism, tendencies that accelerated its dissolution as the People’s Republic of China normalized relations with the US and the Soviet Union fell apart. The New Left admirably prioritized anti-imperialist solidarity from within the heart of empire. However, their critique lives on today as the “campist” doctrine that all rivals to US power must be unquestioningly defended as virtuous anti-imperialists, including regional hegemons like China and Russia. The idea that anti-American countries constituted a coherent, revolutionary bloc has been nonsensical since at least the normalization of Chinese-US relations during the Nixon administration. Today, the position is not only tragic but simulatenously farcical, as well, leading to US socialists supporting the explicitly anti-socialist governments like Iran and denouncing popular social movements around the globe as uniformly reactionary.

Per the Manifesto of The Peoples Want:

These self-proclaimed “anti-imperialists” can seem so far out of step with real movements that when uprisings occur, they rush to apply their abstract interpretations, and deprive those most affected of their ability to make themselves heard… From their supposedly “critical distance” these ideologues, usually based in the West, believe they know better than people on the ground what needs to be done…

Imperial powers such as China and Russia, which rhetorically support the cause of Palestine, are seen as allies, or the lesser evil vis-à-vis the hypocrisy of Western countries, all aligned behind the Israeli occupation. But more “opportune” or “lesser evil” for whom? Why should we tolerate the genocide of Uyghurs in China in order to put an end to the genocide in Gaza? Why should we denounce the Israeli occupation of Palestine on one hand, and turn a blind eye to the counter-insurgency war in Chechnya, Russia’s invasion of Georgia or Ukraine, and vice versa?

To again quote Revolution in the Air, in the era after WWII, “nationalism manifested itself overwhelmingly as a progressive, anti-imperialist and antiracist force.” This was the era of decolonization and wars of national liberation, after all. But it fostered a one-sided valorization of non-Western nationalism and nation-states, one “ill-equipped to deal with other periods (like the present) when many of the most powerful nationalist movements advance conservative social and economic agendas, are indifferent or hostile to pan–Third World or international working class solidarity, foster chauvinist attitudes toward other peoples, and initiate divisive ethnic conflicts.”

Contemporary Western “anti-imperialism” has become a kind of inverted Western chauvinism, with Global North activists writing off thousands or millions of colonized peoples as CIA stooges. “Anti-imperialism” has become a reactionary defense of the capitalist status quo, so long as it’s the status quo prevailing in Tehran or Shenzhen. Those crying for “international solidarity” too often prefer solidarity with party chiefs and prime ministers over solidarity with actual workers, peasants, and students.

But here’s the thing. The Chinese and US economies are now so linked that Trump might upend the global economic system in an attempt to uncouple them. Globalization has created the objective conditions and necessity for real transnational and hemispheric solidarities, now more than ever. Play-acting Cold War fantasies is not enough to confront the machine. To combat a fully globalized capitalism, we need to construct a real global solidarity for our times.

On intercommunalism

I’m not saying anything new here. As early as 1970’s Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, the Black Panther Party’s Huey Newton was developing a new theory of solidarity beyond the nation-state. The Black Panthers started as a revolutionary nationalist party. But capitalist globalization had already permeated the world, making true national liberation impossible. Therefore, Newton said, the Panthers not nationalists or internationalists but intercommunalists.

We say that the world today is a dispersed collection of communities. A community is different from a nation. A community is a small unit with a comprehensive collection of institutions that serve to exist a small group of people. And we say further that the struggle in the world today is between the small circle that administers and profits from the empire of the United States, and the peoples of the world who want to determine their own destinies.

We call this situation intercommunalism. We are now in the age of reactionary intercommunalism, in which a ruling circle, a small group of people, control all other people by using their technology.

In a speech at Boston College in 1974, Newton was even more explicit:

The ruling reactionary circle, through the consequence of being imperialists, transformed the world into what we call “Reactionary Intercommunalism.” They laid siege upon all the communities of the world, dominating the institutions to such an extent that the people were not served by the institutions in their own land. The Black Panther Party would like to reverse that trend and lead the people of the world into the age of “Revolutionary Intercommunalism.” This would be the time when the people seize the means of production and distribute the wealth and the technology in an egalitarian way to the many communities of the world.

We see very little difference in what happens to a community here in North America and what happens to a community in Vietnam. We see very little difference in what happens, even culturally, to a Chinese community in San Francisco and a Chinese community in Hong Kong. We see very little difference in what happens to a Black community in Harlem and a Black community in South America, a Black community in Angola and one in Mozambique. We see very little difference.

Revolutionary intercommunalism simultaneously recognizes the global power of US imperialism while remaining receptive to solidarities between the oppressed communities of San Francisco and Harlem and Hong Kong and Mozambique, all beyond the shell of the nation-state and national boundaries. Revolutionary intercommunalism provided the foundation for the Black Panthers’ groundbreaking solidarity with the gay and women’s liberation movements, as well. Per Newton, revolutionary intercommunalism grew as a worldwide possibility because of the spread of capitalist globalization—the reactionary intercommunalism that, for example, is carving up Barcelona and New York and Mexico City alike for AirBnb vacation rentals. Today, our enemies are truly global. Our friendships must be, as well.

Towards a new solidarity

We can imagine a 21st century intercommunalism that encompasses factory workers in Shenzhen and Dhaka alongside Juárez and Detroit, one that refuses to ignore trans liberation and racial justice as supposed “culture war distractions,” one rooted in neighborhood struggles uniting around the globe.

To take just one example: if you live in a gentrifying neighborhood or have trouble paying rent, you have something in common with folks in Mexico City. And Durban, and London, and Santiago, and Seoul. Not just in that folks are struggling everywhere, but that a globalized and financialized housing market means the same people and institutions are destroying all of these cities.

This is new, and didn’t really exist before finance capital swallowed up swathes of housing stock after the 2008 Great Recession. But we still think of tenants rights and anti-eviction campaigns as fundamentally local initiatives: a city-wide effort, at most.

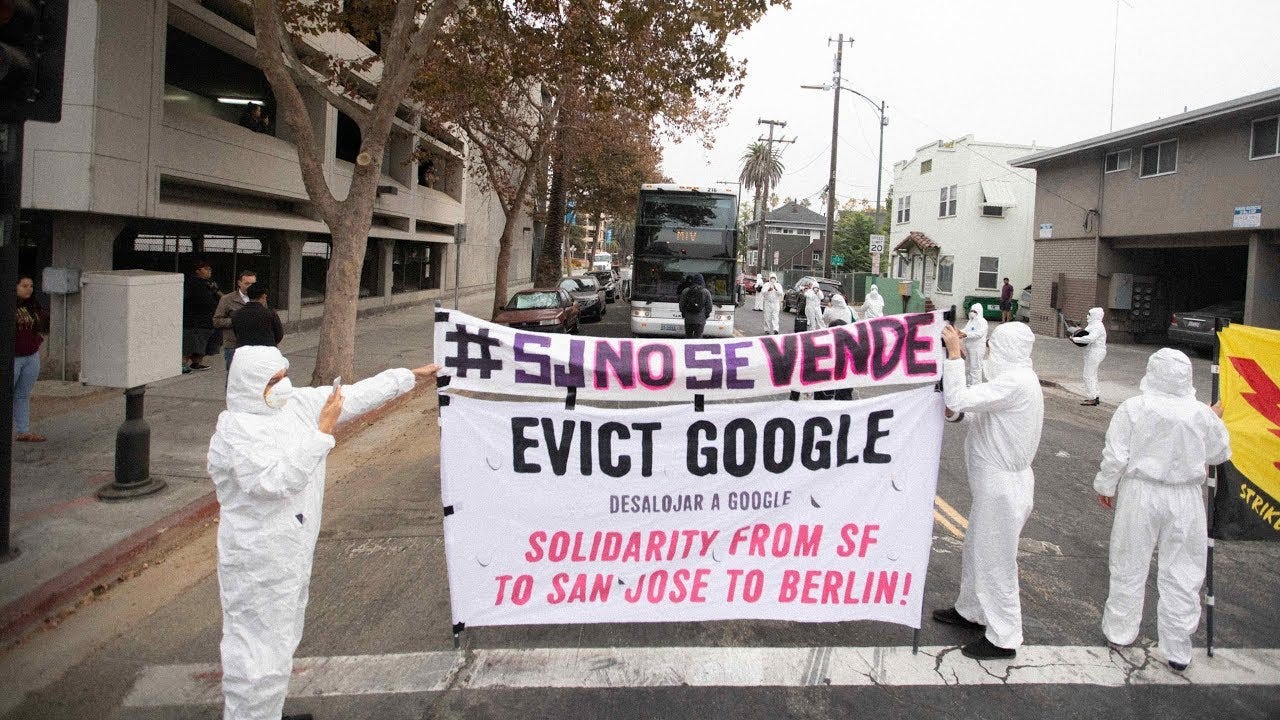

The revolt against gentrification in Mexico City lays the groundwork for a new path: internationalist neighborhood defense. Against the reactionary intercommunalism that evicts Mexican neighborhoods for the profits of American vacation rental companies, global anti-eviction fights are developing the framework for a new revolutionary intercommunalism. This was the thinking motivating a transnational collective action where communities fighting Google developments in Berlin, Toronto, and San José launched coordinated protests with the same messaging and identical banners on two continents. None of the three proposed Google developments was ever completed.

One of the organizers, Katja Schwaller, told me that we need to build “struggles that are adept at thinking the local and global together, with the aim of generating translocal solidarities.” To truly think the local and global simultaenously is much harder than leaning on the “abstract interpretations” criticized by The Peoples Want manifesto because it requires building actual relationships with transnational communities. In requires, in short, real solidarity.

Some questions to ponder: Are our local adversaries global actors? How can we reach out to new friends and allies in unexpected locations? How do global struggles manifest locally? What is my city’s role in neocolonialism and empire? How do we globalize local struggles? How do we localize global ones? What cultural and linguistic skills will allow us to broader our struggle?

How will we, together, win?

For more on global solidarity against the gentrification economy, my book Defying Displacement is out now with AK Press and the Institute for Anarchist Studies.

Read more:

-

Same Struggle, Same Fight. Midnight Sun Magazine.

-

Huey Newton: Speech At Boston College. Workshop for Intercommunal Study.

-

Defying Displacement: Urban Recomposition and Social War. AK Press/IAS.

-

Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che. Verso Books.

-

Manifesto. The Peoples Want.

This post has been syndicated from In Struggle, where it was published under this address.