Joel, involved in anti-nuclear struggles in eastern France, speaks in this interview, conducted by German climate organizers, about “Terres de Luttes” [Territories of Struggle]. Founded in 2020, the association aims to empower struggles against polluting projects across France. Their strategy focuses on building coalitions of local groups confronting large corporations, providing direct support through training, legal assistance and funding. Terres de Luttes’ methods include creating a map of local struggles, conducting sociological studies and organizing coalitions on regional and thematic levels. They offer trainings on communication, mobilization and legal issues, connect activists with lawyers and organize large gatherings. Terres de Luttes’ current strategy for countering rural fascist insurgency involves researching local far-right influence in order to strengthen resistance networks. They are organizing webinars on far-right resistance and plan a thorough study of the “territories.” We are inspired by their concrete approach to the construction of decentralized, territorial power and by their tools-based contribution to a complex ecosystem of rural struggles and projects.

Can you briefly introduce yourself, who are you and how long you have been around?

I’m Joel and I’m involved in anti-nuclear struggles in France, mainly around the resistance against the plans for a huge nuclear waste site in Bure. Over the last 20 years, I was engaged in many social and environmental struggles in Paris and France. For the last three years, I have been working with the association Terres de Luttes. It was created in 2020 by Victor and Chloé, who were very much involved in climate movements before.

Thank you. Why does Terres de Luttes exist? And what are you working towards?

Terres de Luttes aims to empower struggles against polluting, ecocidal projects across France. Our goals are to support those struggles with all they need and connect them to a larger network of environmental struggles. We want to put pressure on the state via a big interconnected network of local struggles.

What are your strategic approaches?

Everywhere in France, we have smaller or bigger collectives with very different political visions and motivations who are fighting destructive projects in their territories. And they are often facing big companies with little means or experience. Terres de Luttes believes that coalescing all these struggles will make them stronger. Often, struggles in different places are against the same companies so we are building up a common approach to better apply pressure. Our main activity is sustaining these coalitions between collectives. Additionally, we also support the small collectives directly to strengthen their action on the ground.

What is your method, your practical approach?

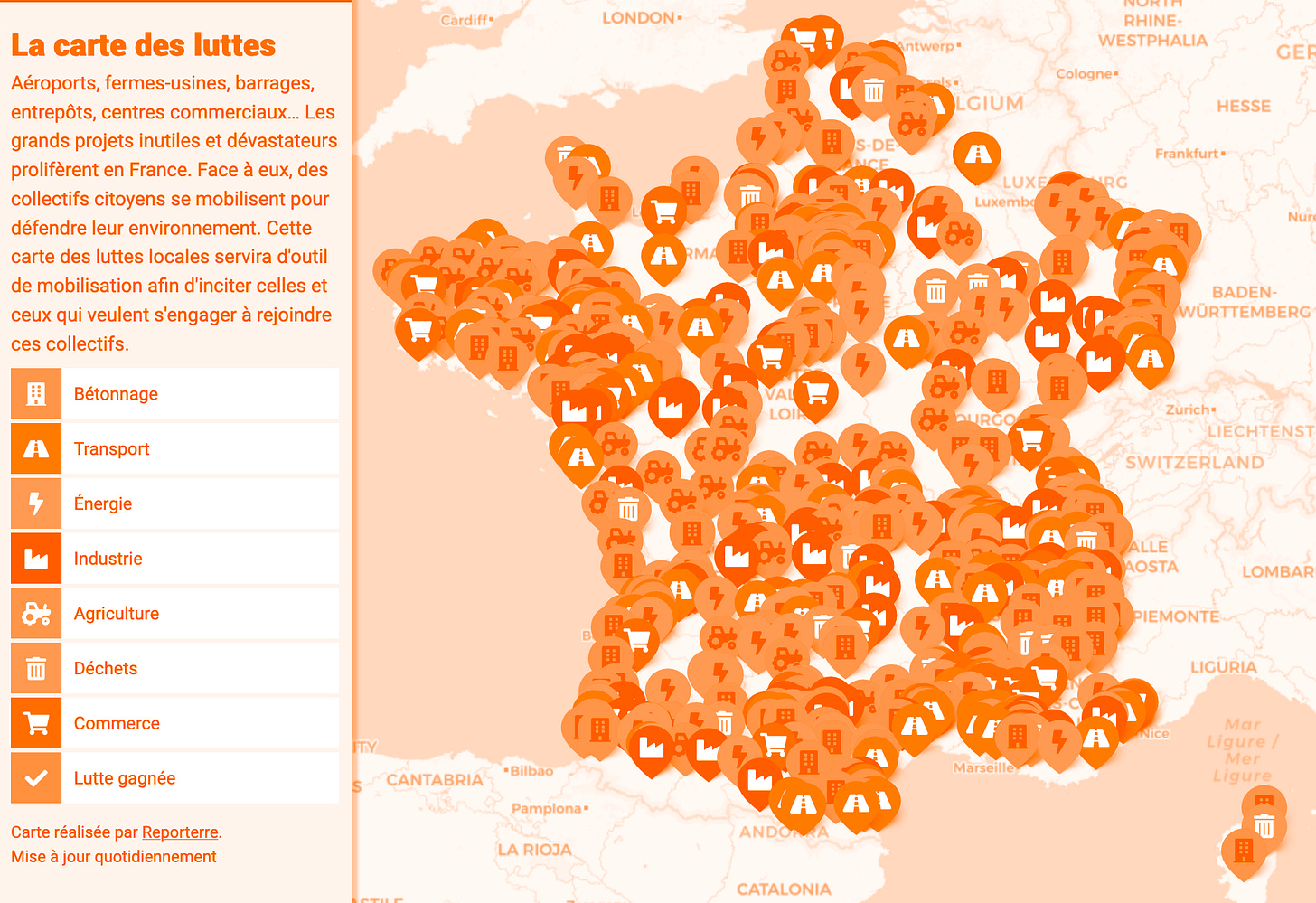

We had several phases. In the beginning, we identified and mapped ongoing struggles. We knew that many of these collectives existed but it was really difficult to know much about them, what they are doing, or the realities of their struggle. So we decided to create an online map in collaboration with reporters from a big French environmental independent media platform (Reporterre). We started with 120 struggles — we have 560 struggles on this map today.

In the second phase, we decided to conduct a huge sociological study on all of these collectives. We wanted to understand how they mobilize, how they communicate, what their challenges are, their successes and defeats, their errors and things they’ve learned, the direct environment and the reality in their territories, their allies or enemies. In total, 80 collectives took part in the study. We published a report to better understand the realities of these local struggles.

After this work, it was easier for us to bring them together and build coalitions. Each of us in Terres de Luttes is also involved in and connected to many local struggles. So we had the legitimacy to initiate or sustain the creation of coalitions in places where they didn’t exist. For example, a coalition against road projects, against big industrial farming projects, for the protection of collective city gardens, for the protection of forests. Today we have around 12 coalitions, with new coalitions created every three months.

We are supporting different forms of coalitions: thematic and regional. It’s important that we bring collectives together who fight the same things, for example against road projects. But we also have to support regional coalitions, so that collectives who are not fighting on the same things but who are active in the same territories can come together.

In our direct support of the collectives, we designed trainings on communication, legal staff, mobilization. But we don’t say to them “that is what you should do”. It’s more about collecting experiences from many collectives and sharing with others: “some people did this in this place and others did this in this place and it was successful; maybe you should do that, maybe you can try this” Rather than explaining to people what we think they should do because each place has its own realities.

We also offer legal support. We have two people in our association who have legal knowledge. So we connect the collectives directly with lawyers or with other legal support structures. Next year we plan to publish a book on environmental appeals in libraries so that everybody can do their own appeals.

We think it is important to gather—to have big gatherings with all these collectives and coalitions. Last year we organized a big meeting in Larzac with 7,000 people. We had 100 workshops and conferences at the same time over four days. It was really, really strong to empower all these collectives and coalitions. It is as if in four days we did the work of three years.

More recently, we decided to create an endowment fund with coalition representatives in the administrative team. We use this fund to finance collectives directly during the whole year with a friendly foundation’s money. In two years we have supported around 40 coalitions and collectives. Recently we also financed several salaries for coordinators of coalitions. We do not want and cannot be inside all the coalitions the whole time. But if we want the coalitions to stay mobilized and reactive, we need some people with paid resources as coordinators.

I love it. And – How can we imagine your concrete political work? What are the important components of your outreach work, your regular offers?

We work on several levels. We have direct political work on the ground with the collectives and the coalitions on a regional and national level. We support the organization of meetings and gatherings. We also open spaces between struggles and big national organizations like trade unions, the farmer unions, and environmental organizations. In those big organizations, we also push a political vision on local struggles in big organizations so they are more concerned about the realities of the local struggles and their actions.

How does your mapping project work? Who can find themselves on it and how can you network?

Many struggles write to us and register directly on the map. We do not have to find them because they come to us—they want to be visible. Others hear about us through our newsletter which many many people and collectives have subscribed to. We also have a toolkit website where we have resources from the struggles. Many collectives are looking for very precise information and find tools on the website. Finally, some join the coalition space because often they have a new project near their homes. The project is, for example, a new road so they’re contacting the coalition on road projects. More often, we are directly contacted by collectives for questions on legal support as many need support for their appeals.

How do you research new local groups’ initiatives, how do you actively approach these groups? How do you win them over?

We don’t have to win them over, I have the feeling, because they come naturally to the coalitions. They need the coalitions because they are often not strong enough to fight alone against the companies. So as soon as they have contacted the coalitions, we bring support. And they know, they’ll do it through this support.

Really nice. How do you see your role in the movement landscape and in the relation to the Earth Uprisings [Les Soulèvements de la Terre]?

As Terres de Luttes, we have an empowerment role in the movement. We are in support of the movement, but we don’t lead the movement. We bring experiences we have on the local struggles in this movement. Within Earth Uprisings, for example, we bring trainings, experiences, facilitate the links with local struggles—that is our main action in the Earth Uprisings. It’s more of a tool-based approach.

Nowadays—talking about the evolution of the movement landscape—it’s a very fragile movement. Several anti-environment laws and many political speeches are criminalizing the environmental activists. It makes us lose environmental activists and our recent victories and successes quickly. We are very aware of the fact that what we are building is fragile, also this big Earth Uprising is fragile. We have to be very prudent about the fact that what we are doing is more to try to empower people locally than to empower the movements between the collectives.

What have been your organizational highlights in the recent times?

We had big concerns about the far-right in the national elections [in July 2024]. We decided to renew our strategic approach totally, to enlarge it and to consider: How could resistance against harmful projects develop other visions? How could they be extended to the world territories and enforce resisting territories? Today, we try to think more about what “resisting territories” could be relative to the far-right: what builds resistance against harmful projects, but also resistance against conservative and far-right visions?

What are your strategies in rural areas also in relation to anti-fascist strategies with the shift of the far-right in France and in Europe?

For now, we have decided to begin in the same way how we have started with Terres de Luttes: we have to have a better understanding from the territories, a better understanding of the far-right establishments, a better understanding who and what is resisting the far-right already. That’s a big part of our reflections at this moment. In a first phase over the next six months, we plan to ask many people on social networks and all our contacts in the local collectives to participate in a big study. We want to understand: what is specific to the territory? How is the economic, immigration, social situation? How are the inequalities and discrimination? We want to understand everything, create a map of the territory. We want to compare this information with information on the far-right networks: what makes the far-right so strong in these territories or less strong in others? In the second part—already three months in—we have begun to have webinars about far-right resistance. In these webinars, we explain what people have tried in some territories to resist the far-right with concrete examples, show what people are doing to fight racism or discrimination in the territories. Each month we plan on having a new webinar with this frame. And in the third phase—starting in six months when we will have the report of the analysis on the territories—we will begin to reenforce the resisting territories as we did for the environmental struggles.

For people who do not know your idea of territory, can you shortly say what do you understand as a territory?

We have the same question. A “territory” can be a department [administrative unit in France] as many people in France are thinking on department or regional level because many things are linked to it. But we don’t want to enclose our vision in this administrative frontier. We know that territories can be cultural, they can have cultural frontiers or geographical realities. We want the possibility of extending our vision about what a territory is. It could be a living territory, where people are close, with the same history, with historical or cultural proximity. For us, a territory is what people are feeling as the land where they are living. And if the land is a department, then we have to work on the department. If the land for them is a region, then we have to work on a regional level.

Interesting. The left theoretician and journalist Raúl Zibechi from Latin America developed the concept about “territories of resistance”. It’s about how mainly the poor classes self-organize and build up resistance, how people build up territories where they resist, produce and create more autonomous and self-government structures and how by this they create these “resistance territories”.

I think we have the same approach. We found five pillars of our strategy. First, it is about enforcing independent places. It could be buildings, struggle places, grounds, farms, every place which is building up a resilience and resistance to the content of Artif-Vision. We have also a pillar on activist networks that exist in a territory: how are they’re acting, how are they connected, how could they be a resistance, how can they build up autonomy and resistance? But we also consider the solidarity, social and associative help networks and connect them more to the activist networks. Our idea is that they’re not simply helping people every day in the cities, like distributing food and other things, but that they are more connected to a strategic vision about how we can change the territories. We want all these actors who feel non-political and not-engaged to be more engaged and more connected to a strategic vision about how to push away the far right. Many of these associations have leftists involved in them but the associations do not identify as leftist. The fourth of our pillars is acting on mutual aid. If we answer the social problems in the territories everywhere, it’s a common political basis. We have to think about how we can act on the realities which makes the far-right so strong in some territories and how we can respond to concerns from the people in the territories. We have to help the people in their concerns, so that they feel concerned by what we defend. The last pillar is auto-defense, more active against far-right and conservative forces: identify, enforce or create antirepression, antifascism, antiracism, fighting discrimination networks locally through cultural, counter cultural or educational frames.

I think it’s useful, yes. In Germany we had a large climate movement with strong mobilizations until 2021. In part very academic and mainly in the cities, little rooted in the countryside and little anchored in rural or agriculture practices. What can we in Germany learn from your approach?

It’s difficult. I had the feeling when I came to Germany that our realities are really different. For example, this countryside question. For the past 40-50 years, many of our struggles in France are built on rural mobilizations, like Notre-Dame-des-Landes, LARZAC and other places against nuclear projects during the ‘70s and ‘80s. We also inherited a very strong farmer resistance network. And another really important aspect in France which supports our struggles a lot is that in the last 30 years—and especially the past 10 years—many young leftist people from the cities decided to live in the countryside. They really pushed leftist vision alternatives in rural areas. On a more marginal level this is also going on in Germany, but not as such a large movement. This is something really strong in our movement landscape and something to think about in the coming years: How can we enlarge this movement back to the countryside?

And in local struggles, how we are connected to the people living in the places where big projects are planned is very important: how can we be more connected with the people living there? Those regions are often places where we don’t want to live, but where we have to be present. We have to imagine how we could live there, how to make it desirable to live there. It’s not easy because in far-right places, as where I live, many activists say: “Oh I would not live there. It’s really hard here.” I think we have to think about how we can strategically make it possible. Because living there is important both in supporting them as well as on this basis we can claim to be part of the land we aim to defend. It is important in direction to those people living here, showing them: “We are part of your land. We are not coming to fight from outside. We are living here, too.”

What questions do you have for the environmental and climate justice movement in Germany?

I would say my question is more to which spaces could we meet more to have a better understanding about our differences; how these differences could make us learn about how we could act in another way that we are not used to thinking about? When I was in Germany, even though I am half-German, I’m not thinking, not living in a German way. And coming to Germany I realized: many things we are doing in France could not work there in the same way, as we, for example have very different ways of activist organizing. But many things could be interesting to share and to see how it could be thought in a German way. For example, the Ende Gelände movement was really inspiring and brought interesting approaches and discussions to some groups in France like the radiaction movement. They organized several gatherings in France, learned a lot about the way Germans were thinking and organizing the struggle. They changed totally the way of acting and thinking their collective in a more German way but on a French mode.

Awesome, it sounds very interesting for me and I think for our readers as well.

And are there events or processes you want to invite groups or persons from German movements to?

Yes, the first one is LES RÉSISTANTES: The LES RÉSISTANTES is that very big gathering we did last year. In 2023 we didn’t have an international part, but in 2025 we want to have an international opening. It could be a good place to meet and to share questions or experiences. LES RÉSISTANTES will happen from 6th to 10th of August 2025, from Thursday to Sunday, in Normandy.1 Secondly, I have the feeling we have to invent more internationalist or European spaces to share experiences. In the last 15 years we totally lost the habit to think in internationalist ways, but it ́s very rich to meet from one country to another to learn about what is working on another way in other countries and regions and to see how we can learn from it.

Great. Thank you so much.

What we’re reading

Dylan Saba on the scenes of escape that link Black and Palestinian anti-colonial struggle, all the more poignant with Assata Shakur’s passing.

A surprising documentary from Business Insider on the data center construction boom.

Kea Krause shares ancient and new reflections on herbal abortion.

Ben Makuch warns of the far-right’s interest in drones for the coming “civil war.”

Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon on ecology as a metaphor for how to transform the internet from a monoculture into an actually-complex web.

Haraami outlines an emerging “partisanship of color” position for revolutionary horizons beyond whiteness and the West, grounded in planetary experiences of autonomy, insurrection, and popular power.

Lily Scherlis brings us into the bizarre world of group relations conferences and asks if there is something in them for us.

A delegation of North American participants contributed to LES RÉSISTANTES, with panels and reflections about struggles on this continent, including the George Floyd Uprising, trans organizing, and the Stop Cop City movement.

This text has been syndicated from Inhabit: Territories.